Great Ecology to Present at 7th International Conference on Eco-Compensation and Payments for Ecosystem Services

November 28, 2018

If a Tree Falls in a Forest, and No One Knows What to Call It, Does It Exist at All?

January 3, 2019

by Liz Clift

Have you seen grasses, like those in the background, on the beach lately?

If you live in an area with ultra low tides during the summer—the answer is likely yes. During ultra low tides, fields of seagrass, like the eelgrass (Zostera marina) pictured above, can become exposed. However, even if you don’t have ultra low tides—and many areas don’t–you may see seagrass wash up when it becomes uprooted from its substrate due to animals feeding, storms, or human activity.

What is Seagrass?

Seagrass is a general term for a variety of underwater flowering plant that belongs to one of four families (Posidoniaceae, Zosteraceae, Hydrocharitaceae, and Cymodoceaceae). Seventy-two species of seagrass are known, and many superficially resemble terrestrial grasses in the Poaceae family (think Kentucky bluegrass [Poa pratensis], which you likely see in urban parks or even in your own yard). Seagrasses, importantly, are like terrestrial grasses, in that they can form roots and rhizomes, rather than having a “holdfast” or floating freely like macroalgae (“seaweed”).

Seagrasses grow in underwater meadows in estuarine or marine environments (not freshwater!) within the photic zone. Like terrestrial prairies or grasslands, seagrass meadows are diverse and productive ecosystems that provide shelter, forage, and breeding grounds for a variety of ecologically important and economically significant species. What you’ll find in fields of seagrass depends on where you live (i.e. tropical versus temperate climates), but some animals that commonly rely on this ecosystem include a variety of juvenile fish, American manatees (Tricherchus manatus), sea turtles, dugongs (Dugong dugong), sea urchins, and crabs.

In addition to providing important habitat, seagrass offers a number of ecosystem services including:

- Habitat for commercially and recreationally important fish;

- Wave protection;

- Oxygen production;

- Coastal erosion protection; and

- a carbon sink.

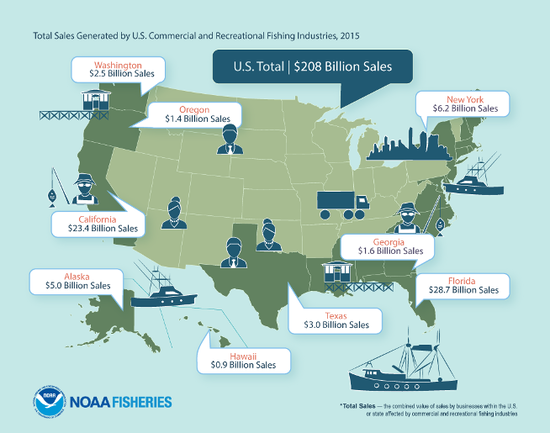

In addition to helping support the $200 billion fishing industry, seagrass meadows account for more than 10% of the ocean’s ability to store carbon—per hectare it is able to store twice as much carbon dioxide as a rain forest, meaning seagrass meadows are able to support the U.S. economy as well as mitigate climate change all at the same time.

Because seagrasses provide so many services and are experiencing global declines, communities are working to enhance and restore seagrass beds, which have been impacted or destroyed by human activities. Since so much of this work happens under water—and therefore out of sight to anyone who isn’t a diver or looking for news about seagrass conservation and restoration—I wanted to highlight a few of the projects occurring around the U.S. to restore seagrass habitat.

Chesapeake Bay

In the Chesapeake Bay, eelgrass beds are essential to maintaining the iconic blue crab (Callinectes sapidus) and wild oyster industries, two of the region’s most valuable fisheries. major seagrass conservation and recovery efforts, including reducing nutrient loads and seeding seagrass have been underway. Since runoff from agriculture is a major component of nutrient pollution, state and federal agencies have been working with farmers to incentivize better practices that has led to decreased nutrient loads in some areas.

In 2010, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) put the Chesapeake Bay on a “pollution diet,” or a Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) to reduce levels of nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment. Six Chesapeake Bay states, and Washington D.C. must have pollution controls in place by 2025. Earlier this year, the EPA released a “check-up” report on the pollution diet. The partnership has fallen short of its nitrogen reduction target; however, this check-up allows the six states and D.C. to use the TMDL information to continue to strive toward the 2025 target and remain accountable.

Concurrently, scientists from the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) having been activity restoring seaside bays in the Chesapeake region. The VIMS Submerged Aquatic Vegetation (SAV) Lab has effectively broadcast 60 million eelgrass seeds over 450 acres over the last 15 years. Given the enhanced water quality in the region and successful reintroduction of eelgrass seed, the species has colonized over 6,000 acres of seagrass meadows (over 10 times its originally seeded area!). This successful restoration effort is one of the largest seagrass restoration projects by size in the world.

Salish Sea

In the Salish Sea, seagrasses provide critical habitat for herring (Clupea harengus pallasii), Dungeness crabs (Metacarcinus magister), and young salmon (all of which support many types of wildlife and are important commercially and recreationally), and six different types of seagrass exist in this area, of which eelgrass is the most widespread.

However, eelgrass (and other seagrass) growth can be hampered by algal blooms, overwater structures because these things block light, sediment loading, shoreline armoring, and vessels anchoring or mooring. Since seagrass is a vital component of this ecosystem, in 2011, an interdisciplinary taskforce developed a strategy with five overarching goals to help Washington state reach its target of expanded eelgrass habitat by 20 percent between by 2020. The goals are:

- Conserve existing eelgrass habitats;

- Reduce environmental stressors to support eelgrass expansion

- Restore and enhance degraded or declining eelgrass meadows;

- Identify research priorities; and

- Expand outreach and education.

The Port of Bellingham, which is part of the Salish Sea has also supported eelgrass recovery efforts, including the redesign of a waterfront park to connect tideflats and eelgrass beds. This project won the American Shore & Beach Preservation Association (ASBPA) award for best restored beach in the Northwest in 2012 and America’s best restored beach in 2009.

Tampa Bay

Since the 1800s, Tampa Bay has lost approximately 80% of its seagrass coverage. Many areas of the Bay were historically affected by direct input of raw sewage from the adjacent communities. This type of nutrient pollution allowed for think mats of algae or seaweed to take over and block all the available light to the seagrasses.

Here, seagrass restoration will provide important fisheries for snook (Centropomus undecimalis), seatrout, and shrimp while also improving water quality. One of Tampa’s approaches to restoration focuses on micropropagation, which is a way to clone plants by collecting the terminal buds, surface-sterilizing them, and then growing them in test tubes with a specific nutrient medium. Once scientists can maintain a rapidly multiplying plant stock in the lab, they will be able to use these plants as a source for additional micropropagation or subculturing (dividing the plant into smaller plantlets and growing plants from these pieces).

This will allow for less disturbance of Tampa’s remaining seagrass beds and allows for more production in less time. Other seagrass restoration efforts include planting and transplanting grasses and repairing scars from anchors or propellers using sediment tubes.

In 1991, when the Tampa Bay Estuary Program was founded, local, state, and federal government set out to clean up and restore seagrasses in Tampa bay. Their goal was to reach 1950 seagrass levels of or nearly double the cover. By 2015, their goal was met and surpassed with seagrass covering over 40,000 acres. The recovery process involved research, planning, enhancing the water quality, and restoring grasses. Work and proper management is still continuing to this day to protect the Bay.

Conclusion

All of these seagrass restoration efforts—and many more that aren’t covered here—serve to improve habitat and forage for a variety of animals, protect shorelines, and trap carbon, among other functions. And, since seagrass exists around the world—and can form meadows large enough to be seen from space, protecting and restoring seagrass anywhere will provide benefits beyond local coastlines. Seagrass restoration is also a two-fold effort where both enhancing water quality and reintroducing the plants are necessary for success.

Keep an eye on our blog for more posts about seagrasses. If you want to learn more about the ecology of seagrasses—as well as their ecosystem services, check out this link.

Unlinked Reference:

Orth, Robert & R. Marion, Scott & Moore, Kenneth & J. Wilcox, David. (2010). Eelgrass (Zostera marina L.) in the Chesapeake Bay Region of Mid-Atlantic Coast of the USA: Challenges in Conservation and Restoration. Estuaries and Coasts. 33. 139-150. 10.1007/s12237-009-9234-0.