Featured Ecologist: Esa Crumb, MS

September 28, 2020

Sanderson Gulch Channel Improvement Project Wins CASFM Award

October 7, 2020

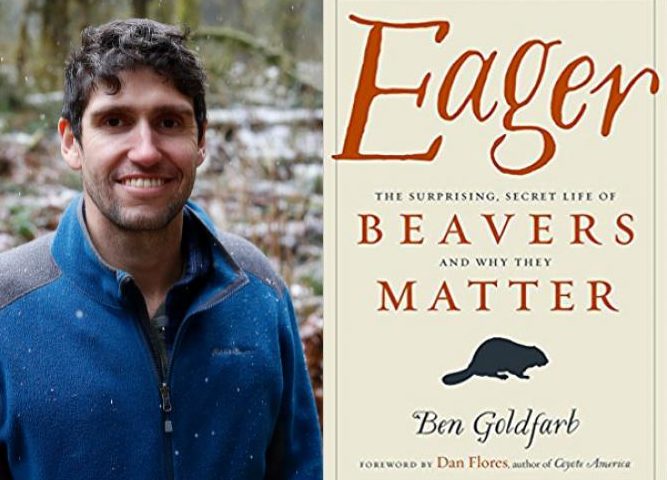

Eager: A Book Review

By Liz Clift

If you were paying attention to our social media in 2018 and 2019, you probably saw us talking about Ben Goldfarb’s Eager: The Surprising, Secret Lives of Beavers and Why they Matter. In no small part, this was because Goldfarb was making the book talk and media interview rounds (not to mention publishing his own writing in the form of articles)—and we saw it as an opportunity to discuss not only a new book focused on ecology, but also an opportunity to introduce people to the benefits of beavers on the landscape.

This year, with the western US wildfires, it seems especially pertinent to return to one of the lessons from Eager—specifically that beavers used to be an integral part of landscapes across the US, and that among many other benefits beavers offer, they can help reduce the incidence and severity of wildfires.

But Eager offers more than just information about how beaver populations can reduce severe wildfires. Goldfarb travels around the US—and to Europe—to consider the impact of beavers on the landscape, how modern and prehistoric beavers literally transformed the places we know today, and interviews people who care about restoring beaver populations—which is important since beavers have been long maligned for “causing” flooding.

As Goldfarb points out, repeatedly, in Eager many of the rich farmlands and prairies we see today were supported by beavers building dams, which spread rivers into their floodplains. These dams trap nutrient rich sediment, which can support food crops. Beaver dams also raise the water table, which provide—and have historically provided—improved subterranean irrigation for crops and ranchlands across the United States. The rich riparian areas created by dams also supported a diversity of plant and animal wildlife that directly and indirectly benefited from beaver dams, including fingering fish (such as trout and salmon), piscivorous birds, wading birds, and large fish-eating mammals, as well as ungulates and others which rely on these pools of water for drinking and forage.

All that interconnectivity with beaver ponds means that the disappearance of beavers—which historically happened through trapping and the fur trade—can stress these ecosystems, which can lead to cascading impacts. Goldfarb lays out example after example of how the eradication of beavers in ecosystems has had negative and lasting impacts on the places we live, work, and play today.

Colonization of the Americas decimated beaver populations—and today only an estimated 10 percent of beaver populations exist relative to the pre-colonial period. This drastically altered ecosystems and impacted not only beavers but all the species that relied on them. And this, in turn has had negative (sometimes devastating) consequences on the US landscape.

It would be easy to create another depressing narrative, given the fact that beaver populations have largely been decimated. However, Goldfarb resists that potential and instead paints a picture of hope—through the stories of Beaver Believers and others who are working together to bring beavers back to the landscape. These stories, scattered throughout the book, are filled with the particular type of optimism that comes from regular people doing good that will likely outlast them. And these stories include all sorts of people—not necessarily just the type of folks you might think of as “conservationists,” including folks working for a small nonprofit in Washington state, to ranchers, to residents of a small California town who have created an entire festival centering beavers.

This is perhaps one of the greatest strengths of Eager. Goldfarb’s portrait of beavers—and why they matter—can help contextualize the efforts to save the species and provide supportive environments for their repatriation. But it’s the stories of people once again embracing the presence of beavers and the benefits of living near beavers that has helped inspire more people to move toward beaver conservation. It’s the work of these people—often average people like you and I—that can help normalize the presence of beavers on the land, advocate for beavers in our cities and towns, and demand that developers consider beavers when planning a landscape—because it isn’t just about beavers themselves (and it never has been). It’s about the well-being all of all of us.